Muhajir people

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The

Muhajir people (also spelled

Mahajir and

Mohajir) (

Urdu:

مہاجر,

Arabic:

مهاجر) are

Muslim immigrants, of multi-ethnic origin, and their descendants, who migrated from various regions of

India after the

Partition of India to settle in the newly independent state of Pakistan.

[7][8][9][10][11] Although some of them speak different languages at the native level, they are primarily identified as native

Urdu speakers and hence are called Urdu-speaking people.

Etymology

The Urdu term

muhājir (

Urdu:

مہاجر) comes from the Arabic

muhājir (

Arabic:

مهاجر), meaning an "immigrant",

[12][13][14] and the term is associated in early

Islamic history to the

migration of

Muslims. After the

independence of Pakistan, a significant number of Muslims emigrated or were out-migrated from territory that remained

India.

In the aftermath of partition, a huge population exchange occurred

between the two newly formed states. In the riots which preceded the

partition in the Punjab region, between 200,000 and 2 000,000 people

were killed in the retributive genocide.

[15][16] UNHCR estimates 14 million Hindus, Sikhs and Muslims were displaced during the partition; it was the largest

mass migration in human history.

[17][18][19]

Most of those migrants who settled in the Punjab province of Pakistan came from the neighbouring Indian regions of

Punjab,

Haryana,

Himachal Pradesh, and

Delhi while others were from

Jammu and Kashmir,

Rajasthan and the

United Provinces.

Migrants who moved to the

Sindh province of

Pakistan came from what then were the British Indian provinces of

Bombay,

Central Provinces,

Berar, and the

United Provinces, as well as the

princely states of

Hyderabad,

Baroda,

Kutch and the

Rajputana Agency. Most of these migrants settled in the towns and cities of

Sindh, such as

Karachi,

Hyderabad,

Sukkur and

Mirpurkhas.

Many spoke

Urdu, or dialects of the language such as

Dakhani,

Khariboli,

Awadhi,

Bhojpuri,

Mewati,

Sadri and

Marwari

and Haryanvi and became commonly known as Muhajirs. Over a period of a

few decades, these disparate groups sharing the common experience of

migration, and political opposition to the military regime of

Ayub Khan and his civilian successor

Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto evolved or

assimilated into a distinct ethnic grouping.

[20]

Origin and conversion theories

Considerable controversy exists both in scholarly and public opinion as to how conversion to Islam came about in the

Indian subcontinent, typically represented by the following schools of thought:

[21]

- Conversion came from Buddhists and the masses of conversions of lower caste Hindus as they were the vulnerable and enticed by uniformity under Islam. (See Indian caste structures).[22]

- Conversion was a combination, initially by violence, threat or other

pressure against the person followed by a genuine change of heart.[21]

- As a socio-cultural process of diffusion and integration over an extended period of time into the sphere of the dominant Muslim civilization and global polity at large.[22]

- That conversions occurred for non-religious reasons of pragmatism

and patronage such as social mobility among the Muslim ruling elite.[21][22]

Delhi Sultanate and Mughal Empire

Muslims from Northern India in areas that are now the states of

Delhi,

Bihar and

Uttar Pradesh were of heterogeneous origin. The

Hindustani-speaking Muslim people of Pakistan and India have diverse roots.

[citation needed] During the era of

Delhi Sultanate and later the

Mughal Empire,

large parts of the Indian Subcontinent came under the direct or

indirect rule of Muslim dynasties of the foreign Turkic origin from

Central Asia. This era saw conversion of part of native lower caste

Hindu population(See

Indian caste structures) to Islam.

[21]

Conversion was a combination of various factors such as violence,

threat or other pressure by the foreign, Muslim ruling class on the

natives, followed by a genuine change of heart.

[21]

Conversions also happened as a socio-cultural process of diffusion and

integration over an extended period of time into the sphere of then

dominant Muslim civilization and global polity at large.

[22] and for non-religious reasons of pragmatism and patronage such as social mobility among the Muslim ruling elite.

[21][22]

In addition to conversions, a population of Muslim refugees,

nobles,

technocrats,

bureaucrats, soldiers,

traders, scientists, architects,

artisans, teachers, poets, artists, theologians and

Sufis from the rest of the

Muslim world migrated and settled in the area. At the court of

Sultan Iltemish in Delhi, the first wave of these Muslim refugees, escaping from the

Mongol invasion of Central Asia by the hordes of

Genghis Khan, brought individuals to the subcontinent from the aforementioned region.

[citation needed] Mughal Emperor

Babur defeated the

Lodi dynasty with

Tajik,

Turkic and

Uzbek soldiers and nobility.

The Rohilla leader Daud Khan was awarded the

Katehar (later called

Rohilkhand) region in the then

northern India by Mughal emperor

Aurangzeb (ruled 1658–1707) to suppress the Hindu

Rajputs,

who were earlier allied with the Mughals. Originally, some 20,000

soldiers from various Afghan Pashtun tribes were hired by Mughals to

provide soldiers to the Mughal armies. Their performance was appreciated

by Mughal emperor Aurangzeb Alamgir, and an additional force of 25,000

Pashtuns were recruited from

Afghanistan, Many of these Afghan Pashtuns settled in northern India and also brought their families from Afghanistan.

[citation needed] Due to the large settlement of Rohilla

Afghans, the Katehar region gained fame as Rohilkhand.

[citation needed] Bareilly was made the capital of the Rohilkhand state and it became Afghan majority city with

Gali Nawaban as the main royal street. Other important cities were

Moradabad,

Rampur,

Shahjahanpur,

Badaun, and others.

[23][24]

These diverse ethnic, cultural and linguistic Muslim groups of foreign

and native origin, merged over the centuries to the form the

Urdu-speaking Muslim population.

[citation needed]

The

Kayastha community had historically been involved in the occupations of land

record keeping and accounting. Many Hindu Kayasthas found favour with the Mughal elite for whom they acted as

Qanungos. This close association led to the conversion of some members of the Kayastha community to

Islam. The

Muslim Kayasths speak local dialects, in addition to the Urdu language

[25] while they also speak

Sindhi in Pakistan. The Kayastha converts, incidentally uses

Siddiqui,

Shaikh,

Usmani and

Farooqi as their surnames, and claim themselves as belonging to the Shaikh community.

[26]

Decline of Mughal rule

The

Maratha Empire

(1674–1818) ruled large parts of India following the decline of the

Mughals. Mountstart Elphinstone termed this a demoralizing period for

the Muslims, as many of them lost the will to fight against the Maratha

Empire.

[27][28][29] The Maratha empire at its peak stretched from Tamil Nadu in the south to the Afghan border in the north.

[30][31][32]

In early 1771, Mahadji, a notable Maratha general, recaptured Delhi and

installed Shah Alam II as the puppet ruler on the Mughal throne. In

north India, the Marathas thus regained the territory and the prestige

lost as result of the defeat at the

Panipat in 1761.

[33] Mahadji ruled the Punjab, as it used to be a Mughal territory, and Sikh sardars and other rajas of the

cis-Sutlej region paid tributes to him.

[34] A considerable portion of the Indian subcontinent came under the sway of the

British Empire after the

Third Anglo-Maratha War, which ended the Maratha Empire in 1818.

In northwest India, in the Punjab,

Sikhs developed themselves into a powerful force under the authority of twelve Misls. By 1801,

Ranjit Singh captured

Lahore and ended Afghan rule in North West India.

[35] In Afghanistan,

Zaman Shah Durrani was defeated by powerful

Barakzai chief Fateh Khan, who appointed

Mahmud Shah Durrani as the new ruler of Afghanistan and appointed himself as Wazir of Afghanistan.

[36] The Sikhs, however, were now stronger than the Afghans and started to annex Afghan provinces. The biggest victory of the

Sikh Empire over the

Durrani Empire came in the

Battle of Attock, fought in 1813 between the Sikhs and the Wazir of Afghanistan Fateh Khan and his younger brother

Dost Mohammad Khan.

The Afghans were routed by the Sikh army and the Afghans lost over

9,000 soldiers in this battle. Dost Mohammad was seriously injured,

whereas his brother Wazir Fateh Khan fled back to

Kabul fearing that his brother was dead.

[37] In 1818 they

[who?] slaughtered Afghans and Muslims in the trading city of

Multan, killing Afghan governor Nawab Muzzafar Khan and five of his sons in the

Siege of Multan.

[38] In 1819 the last Indian Province of

Kashmir was conquered by Sikhs who registered another victory over weak Afghan General Jabbar Khan.

[39] The

Koh-i-Noor

diamond was also taken by Maharaja Ranjit Singh in 1814. In 1823, a

Sikh Army routed Dost Mohammad Khan, the Sultan of Afghanistan, and his

brother Azim Khan at Naushera (near Peshawar). By 1834, the Sikh Empire

extended up to the

Khyber Pass.

Hari Singh Nalwa,

a Sikh general, remained the governor of Khyber Agency till his death

in 1837. He consolidated Sikh control in tribal provinces. The

northernmost Indian territories of

Gilgit,

Baltistan and

Ladakh was annexed between 1831–1840.

[40]

British Rule

Prior to 1857, British territories were controlled by the

East India Company.The company maintained the fiction of running the territories on behalf of the Mughal empire.The crushing defeat of

Mutineers

in 1857 -1858 led to the abolition of the Mughal empire and the British

government taking direct control of the Indian territories

[41].

In the immediate aftermath of the rebellion, upper-class Muslim were

targeted by the British, as some of the leadership for the war came from

this community based in areas around Delhi and what is now Uttar

Pradesh; thousands of them and their families were shot, hanged or blown

by canon.Per Mirza Ghalib, even women were not spared because the rebel

soldiers disguised themselves as women

[42].

The

Pakistan movement,

to constitute a separate state comprising the Muslim-majority

provinces, was pioneered by the Muslim elite and many notables of the

Aligarh Movement. It was initiated in the 19th century when Sir

Syed Ahmed Khan expounded the cause of Muslim autonomy in

Aligarh. Many Muslim nobles such as

nawabs

(aristocrats and landed gentry) supported the idea. As the idea spread,

it gained great support amongst the Muslim population and in particular

the rising middle and upper classes.

The Muslims launched the movement under the banner of the

All India Muslim League

and Delhi was its main centre. The headquarters of All India Muslim

League (the founding party of Pakistan) was based there since its

creation in 1906 in

Dhaka

(present day Bangladesh). The Muslim League won 90 percent of reserved

Muslim seats in the 1946 elections and its demand for the creation of

Pakistan received overwhelming popular support among Indian Muslims.

[43][44][45]

Migration

The independence of Pakistan in 1947 saw the settlement of Muslim refugees fleeing from

anti-Muslim pogroms from India

[citation needed]. Most of the Muhajirs now live in

Karachi which was the first capital of Pakistan. After the independence of Pakistan in 1947, the minority Hindus and Sikhs

migrated to India while the Muslim

refugees from India settled in Karachi.

[46] In Karachi, the Urdu-speaking Muhajirs form the majority of the population and give the city its

northern Indian atmosphere.

[47]

The Muslim refugees lost all their land and properties in India when

they fled and some were partly compensated by properties left by Hindus

that migrated to India. The Muslim

Gujaratis,

Konkani,

Hyderabadis,

Marathis and

Rajasthanis fled India and settled in Karachi. There is also a sizable community of

Malayali Muslims in Karachi (the

Mappila), originally from

Kerala in

South India.

[48]

Many Muslim families from India continued migrating to Pakistan

throughout the 1950s and even early 1960s. Research has found that there

were three predominant stages of Muslim migration from India to West

Pakistan. The first stage lasted from August–November 1947. In this

stage of migration the Musim immigrants originated from East Punjab,

Delhi, the four adjacent districts of U.P. and the princely states of

Alwar and Bharatpur which are now part of the present state of

Rajasthan.

[49] The violence affecting these areas during partition precipitated an exodus of Muslims from these areas to Pakistan.

The second stage (December 1947-December 1971) of the migration was from areas currently in Indian states of

U.P.,

Delhi,

Gujarat,

Rajasthan,

Maharashtra,

Madhya Pradesh,

Karnataka,

Telangana,

Andhra Pradesh,

Tamil Nadu and

Kerala.

[49]

The third stage which lasted between 1973 and the 1990s was when

migration levels of Indian Muslims to Pakistan was reduced to its lowest

levels since 1947

[citation needed].

In 1959 the International Labour Organisation (ILO) published a

report stating that between the period of 1951-1956, a number of 650,000

Muslims from India relocated to West Pakistan.

[49]

However, Visaria (1969) raised doubts about the authenticity of the

claims about Indian Muslim migration to Pakistan, since the 1961 Census

of Pakistan did not corroborate these figures. However, the 1961 Census

of Pakistan did incorporate a statement suggesting that there had been a

migration of 800,000 people from India to Pakistan throughout the

previous decade.

[50]

Of those who had left for Pakistan, most never came back. The Indian

Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru conveyed distress about the continued

migration of Indian Muslims to West Pakistan:

[49]

There has...since 1950 been a movement of some Muslims from India to

Western Pakistan through the Jodhpur-Sindh via Khokhropar. Normallly,

traffic between India and West Pakistan was controlled by the permit

system. But these Muslims going via Khokhropar went without permits to

West Pakistan. From January 1952 to the end of September, 53,209 Muslim

emigrants went via Khokhropar....Most of these probably came from the

U.P. In October 1952, up to the 14th, 6,808 went by this route. After

that Pakistan became much stricter on allowing entry on the introduction

of the passport system. From the 15th of October to the end of October,

1,247 went by this route. From the 1st November, 1,203 went via

Khokhropar.[49]

Indian Muslim migration to West Pakistan continued unabated despite

the cessation of the permit system between the two countries and the

introduction of the passport system between the two countries. The

Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru once again expressed concern at

the continued migration of Indian Muslims to West Pakistan in a

communication to one of his chief ministers (dated 1, December 1953):

A fair number of Muslims cross over to Pakistan from India, via

Rajasthan and Sindh daily. Why do these Muslims cross over to Pakistan

at the rate of three to four thousand a month? This is worth enquiring

into, because it is not to our credit that this should be so. Mostly

they come from Uttar Pradesh, Rajasthan or Delhi. It is evident that

they do not go there unless there is some fear or pressure on them. Some

may go in the hope of employment there. But most of them appear to feel

that there is no great future for them in India. I have already drawn

your attention to difficulties in the way of Government service. Another

reason, I think, is the fear of Evacuee Property Laws [EPL]. I have

always considered these laws both in India and Pakistan as most

iniquitous. In trying to punish a few guilty persons, we punish or

injure large numbers of perfectly innocent people...the pressure of the

Evacuee Property Laws applies to almost all Muslims in certain areas of

India. They cannot easily dispose of their property or carry on trade

for fear that the long arm of this law might hold them down in its grip.

It is this continuing fear that comes in the way of normal functioning

and normal business and exercises a powerful pressure on large numbers

of Muslims in India, especially in the North and the West.[49]

In 1952 the passport system was introduced for travel purposes

between the two countries. This made it possible for Indian Muslims to

legally move to Pakistan. Pakistan still required educated and skill

workers to absorb into its economy at the time, due to relatively low

levels of education in the regions which became part of Pakistan. As

late as December 1971, the Pakistan High Commission in New Delhi was

authorized to issue documents to educationally qualified Indians to

migrate to Pakistan.

[49]

The legal route was taken by unemployed but educated Indian Muslims

seeking better fortunes, however poorer Muslims from India continued to

go illegally via the Rajasthan-Sindh border until the 1965

India-Pakistan war when that route was shut. After the conclusion of the

1965 war, most Muslims who wanted to go to Pakistan had to go there via

the India-East Pakistani border. Once reaching Dhaka, most made their

way to the final destination-Karachi. However, not all managed to reach

West Pakistan from East Pakistan.

Indian Muslim migration to Pakistan declined drastically in the

1970s, a trend noticed by the Pakistani authorities. On June 1995,

Pakistan's interior minister, Naseerullah Babar, informed the National

Assembly that between the period of 1973-1994, as many as 800,000

visitors came from India on valid travel documents. Of these only 3,393

stayed back.

[49]

In a related trend, intermarriages between Indian and Pakistani Muslims

have declined sharply. According to a November 1995 statement of Riaz

Khokhar, the Pakistani High Commissioner in New Delhi, the number of

cross-border marriages has declined from 40,000 a year in the 1950s and

1960s to barely 300 annually.

[49]

A large number of Urdu-speaking muslims from Bihar went to

East Pakistan

after independence of India and Pakistan in 1947.After the formation of

Bangladesh in 1971, the Biharis maintained their loyalty to Pakistan

and wanted to leave Bangladesh for Pakistan. Majority of these people

are still waiting,however, 178,00 have been repatriated. In 2015, the

Pakistani government stated that the remaining '

Stranded Pakistanis' are not its responsibility but rather the responsibility of Bangladesh.

[51]

Upon arrival to West Pakistan, many refugees hastened to change their surnames, taking on the names

Sayyid or

Qureshi,

for example, in order to lay claim to a more prestigious lineage.

Others played on the proximity of the names Ansars (descendents of

Medina, ashrafs) and Ansaris (caste of weavers, ajlafs). The partition

brought about quite exceptional circumstances that facilitated the

implementation of these strategies.

[52]

Politics

1947–1958

Upon

arrival in Pakistan, the Muhajirs did not assert themselves as a

separate ethnic identity but were at the forefront of trying to

construct an Islamic Pakistani identity.

[53]

Muhajirs dominated the bureaucracy of Sindh in the early years of the

Pakistani state, largely due to their higher levels of educational

attainment.

[54]

The critical early years of Pakistan were facilitated by the experience

that many Muhajirs had both in politics and in higher education.

Many Urdu-speaking people had higher education and civil service experience from working for the

British Raj and

Muslim princely states. From 1947 to 1958, Urdu-speaking Muhajirs held more jobs in the

Government of Pakistan

than their proportion in the country's population (3.3%). In 1951, of

the 95 senior civil services jobs, 33 were held by Urdu-speaking people

and 40 by

Punjabis.

Gradually, as education became more widespread,

Sindhis and

Pashtuns, as well as other ethnic groups, started to take their fair share of the pool in the bureaucracy.

[55]

1958–1970

On 27 October 1958,

General Ayub Khan stage a

coup and imposed

martial law across Pakistan.

[56] The percentage of Urdu-speaking people in the

civil service declined while the percentage of Pashtuns in it increased. In the

presidential election of 1965, the

Muslim League split in two factions: the

Muslim League (Fatima Jinnah) supported

Fatima Jinnah, the younger sister of

Muhammad Ali Jinnah, while the

Convention Muslim League

supported General Ayub Khan. The Urdu-speaking people had supported the

Muslim League before the independence of Pakistan in 1947 and now

supported the

Muslim League of Fatima Jinnah. The

electoral fraud of the 1965 presidential election and a post-election triumphal march by

Gohar Ayub Khan, the son of General Ayub Khan, set off ethnic clashes between Pashtuns and Urdu-speaking people in Karachi on 4 January 1965.

[57]

Four years later on 24 March 1969, President Ayub Khan directed a letter to

General Yahya Khan, inviting him to deal with the tense political situation in Pakistan. On 26 March 1969, General Yahya appeared on

national television and proclaimed martial law over the country. Yahya subsequently abrogated the

1962 Constitution, dissolved

parliament, and dismissed President Ayub's civilian officials.

[58]

1970–1977

The

Pakistani general election, 1970 on 7 December 1970,

Awami League won the elections. The Urdu-speaking people voted for the

Jamaat-e-Islami Pakistan and

Jamiat Ulema-e-Pakistan. The

Pakistan Peoples Party government

nationalization

the financial industry, educational institutions and industry. The

nationalization of Pakistan's educational institutions, financial

institutions and industry in 1972 by Prime Minister

Zulfikar Ali Bhutto

of Pakistan Peoples Party impacted the Muhajirs hardest as their

educational institutions, commerce and industries were nationalized

without any compensation.

[59] Subsequently, the quota system was introduced and this limited their access to education and employment.

In 1972 language riots broke out between Sindhis and Urdu-speakers

after the passage of the "Teaching, Promotion and use of Sindhi

Language" bill in July 1972 by the

Sindh Assembly; which declared

Sindhi as the only official language of Sindh. Due to the clashes, Prime Minister

Zulfikar Ali Bhutto compromised and announced that

Urdu and

Sindhi

would both be official languages of Sindh. The making of Sindhi as an

equal language to Urdu for official purposes frustrated the

Urdu-speaking people as they did not speak the

Sindhi language.

[55]

1977–1988

In the

1977 Pakistani general election,

Jamaat-e-Islami Pakistan and

Jamiat Ulema-e-Pakistan joined in a coalition named the

Pakistan National Alliance. The Urdu-speaking people voted mostly for the Pakistan National Alliance.

[60] The

electoral fraud by Pakistan Peoples Party caused protests across the country. On July 5, 1977,

Chief of Army Staff General

Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq led a coup d'etat against Bhutto and imposed

martial law.

Zain Noorani, a prominent member of the

Memon community, was appointed as Minister of State for Foreign affairs with the status of a Federal Minister in 1985.

1988–1993

The Muhajirs (Urdu-speakers) of Pakistan were largely settled in the

Sindh province,

particularly in the province's capital, Karachi, where the Muhajirs

were in a majority. As a result of their domination of major Sindhi

cities, there had been tensions between Muhajirs and the native Sindhis.

The Muhajirs, upon their arrival in Pakistan, soon joined the

Punjabi-dominated ruling elite of the new-born country due to their high

rates of education and urban background.

[54] They possessed the required expertise for running Pakistan's nascent bureaucracy and economy.

[citation needed] Although the Muhajirs were, socially, urbane and liberal they sided with the country's religious political parties such as

Jamiat Ulema-i-Pakistan (JUP).

[60]

The dichotomy between the Muhajirs’ social and political dispositions

was a result of the sense of insecurity that the community felt in a

country where the majority of its inhabitants were ‘natives.’ Lacking

the historical and cultural roots of native Pakistani ethnicities, the

Mohajirs backed the state's project of constructing a homogenous

national identity that repulsed ethnic sentiment.

[61]

The Mohajirs also echoed the views of the religious parties that

eschewed pluralism and ethnic identities and propagated a holistic

national unity based on the commonality of the Islamic faith followed by

the majority of Pakistanis. By the time of Pakistan's first military

regime (Ayub Khan, 1958), the Muhajirs had already begun to lose their

influence in the ruling elite.

[60][61] With the

Baloch,

Bengali and

Sindhi nationalists distancing themselves from the state's narratives of nationhood, Ayub (who hailed from what is now the

Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province),

slowly began to pull the Pakhtuns into the mainstream areas of the

economy and politics. This caused the Muhajirs’ to agitate against the

Ayub dictatorship from the early 1960s onwards.

[57]

Muhajirs had decisively lost their place in the ruling elite, but

they were still an economic force to reckon with (especially in urban

Sindh). When a Sindhi, Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, became the country's head of

state in December 1971, the Muhajirs feared that they would be further

side-lined, this time by the economic and political resurgence of

Sindhis

under Bhutto. In response the Mohajirs enthusiastically participated in

the 1977 right-wing movement against the Bhutto regime (which was

largely led by the religious parties). The movement was particularly

strong among Karachi's middle and lower-middle-classes (and aggressively

backed by industrialists, traders and the shopkeepers).

[55]

But the success of the PNA (Pakistan National Alliance) movement did

not see the Muhajirs finding their way back into the ruling elite, even

though the Jamaat-i-Islami became an important player in the first

cabinet of

General Zia regime that came to power through a

military coup

in July 1977. Disillusioned, some young Muhajir politicians came to the

conclusion that their community had been exploited by religious

parties, and that these parties had used the shoulders of the Muhajirs

to climb into the corridors of power. This galvanised the formation of

the All Pakistan Mohajir Students Organisation (in 1978) and then the

Mohajir Qaumi Movement (MQM) in 1984. Its founders,

Altaf Hussain and

Azeem Ahmed Tariq, decided to organise the Mohajir community into a cohesive ethnic whole.

For this, they found the need to break away from the community's

tradition of being politically allied to the religious parties, and

politicise the Muhajirs’ more liberal social dynamics and character. The

Muhajir dichotomy between social liberalism and political conservatism

was dissolved and replaced with a new identity-narrative concentrating

on the formation of Muhajir ethnic nationalism that was socially and

politically liberal but fiscally conservative and provincial in outlook.

The project was a success. The MQM successfully broke the electoral

hold of the religious parties in Karachi and subsequently re-invented

the Muhajirs of Sindh as a distinct ethnic group. By 1992, the MQM had

become Sindh's second largest political party (second to the PPP). But

as the city's economics and resources continued to come under stress due

to the increasing migration to the city from within Sindh, Khyber

Pakhtunkhwa and the Punjab, corruption in the police and other

government institutions operating in Karachi grew two-fold.

The need to use power to tilt the political and economic facets of

the city towards the Urdu-speaking community's interests became visible.

Thus emerged the militant wings from the city's prominent political

groups. These cleavages saw the MQM ghettoising large swaths of the

city's Muhajirs in areas where it ruled supreme. This had an adverse

impact. It replaced the pluralistic and enterprising disposition of the

Muhajirs with a besieged mentality that expressed itself in an awkwardly

violent manner attracting the concern and then the wrath of the state

and two governments in the 1990s.

In 2002, the MQM began to re-invent itself after the crises of the

preceding decade when it decided to end hostilities with the state by

allying itself with the

General Musharraf

dictatorship (1999–2008). The party had already weaned away the Muhajir

community from the concept of Pakistani nationhood propagated by the

religious parties. Now it added two more dimensions to Muhajir

nationalism. It began to explain the Muhajirs as ‘Urdu-speaking Sindhis’

who were connected to the Sindhi-speakers of the province in a

spiritual bond emerging from the teachings of Sindh's ‘patron saint’,

Shah Abdul Latif.

This was the

MQM's way of resolving the Muhajirs’ early failures to fully integrate into

Sindhi culture.

The other dimension that emerged during this period among the Muhajir

community (through the MQM), was to address the disposition of Muhajir

identity in the (urban) Muhajir-majority areas of Sindh. This dimension

explains Muhajir nationalism in the context of Pakistan's status of

being a Muslim-majority state. It expresses Muhajir nationalism through a

version of socio-political liberalism based on the modern reworking of

19th century ‘rational and progressive Islam’ (of the likes of

Sir Syed Ahmed Khan).

It sees spiritual growth as a consequence of material growth (derived

from modern free enterprise, science, the arts and the consensual

de-politicisation of faith).

Demographics and distribution within Pakistan

Census History of Urdu Speakers in Pakistan[62]

| Year |

Population of Pakistan |

Percentage |

Urdu Speakers |

| 1951 |

33,740,167 |

07.05% |

2,378,681 |

| 1961 |

42,880,378 |

07.56% |

3,246,044 |

| 1972 |

65,309,340 |

07.60% |

4,963,509 |

| 1981 |

84,253,644 |

07.51% |

6,369,575 |

| 1998 |

132,352,279 |

07.57% |

9,939,656 |

Provinces of Pakistan by Urdu speakers (1998)

| Rank |

Division |

Urdu speakers |

Percentage |

| – |

Pakistan |

9,939,656 |

07.57% |

| 1 |

Sindh |

6,407,596 |

21.05% |

| 2 |

Punjab |

3,320,320 |

04.07% |

| 3 |

Khyber Pakhtunkhwa |

100,320 |

00.95% |

| 4 |

Islamabad Capital Territory |

81,409 |

10.11% |

| 5 |

Balochistan |

63,032 |

00.96% |

| 6 |

Federally Administered Tribal Areas |

5,717 |

00.18% |

Muhajir diaspora

Many Muhajirs have emigrated from Pakistan and have settled permanently in Europe, North America and

Australasia. There are also significant number of Muhajirs who are working in the Middle East, especially in the

Persian Gulf countries:

Regions with significant populations of Urdu speakers

Culture and lifestyle

The rich heritage brought by migrants from the urban centres of India, such as

Lucknow,

Delhi,

Hyderabad and

Bombay,

which had been seats of Islamic culture and learning for centuries, was

to have a major influence on the cities of Pakistan, especially

Karachi. The notable 20th-century Islamic scholar/author

Muhammad Hamidullah was involved in formulating the first

Constitution of Pakistan.

Language

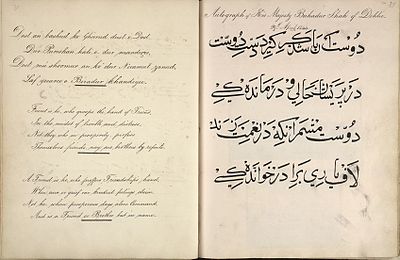

The phrase

Zaban-e Urdu-e Mualla ("The language of the exalted") written in

Nastaʿlīq script.

The original language of the Mughals had been a

Turkic language. After their migration to the area, they came to adopt

Persian and later Urdu. Urdu is an

Indo-European language, and in the

Indo-Aryan subdivision. The word

Urdu is believed to be derived from the Turkish word 'Ordu', which means

army (Hence Urdu is sometimes called "Lashkarī zabān", Persian for "the language of the army"). It was initially called

Zaban-e-Ordu or

language of the army and later just

Urdu. The word 'Ordu' was later

Anglicised

as 'Horde'. Urdu was heavily influenced by Persian and Arabic and

somewhat by Turkish; however, its grammatical structure is based on old

Parakrit or Sanskrit. Urdu speakers have adopted this language as their

mother tongue for several centuries.

Urdu has been the medium of the literature, history and journalism of

Muslims in the area during the last 400 years. Most of the work was

complemented by ancestors of native Urdu speakers in the region. The

Persian language, which was the official language during and after the

reign of the Mughals,

was slowly starting to lose ground to Urdu during the reign of Aali

Gohar Shah Alam II. Subsequently, Urdu developed rapidly as the medium

of literature, history and journalism of South Asian Muslims. Most of

the literary and poetic work was complemented by various historic poets

of mughal and subsequent era, among which

Mir Taqi Mir,

Khwaja Mir Dard,

Mir Amman Dehalvi,

Mirza Ghalib,

Bahadur Shah II Sir Syed Khan and

Maulana Hali

are the most notable ones. The Persian language, which had its roots

during the time of Moguls, was then replaced later by Urdu. Mogul kings

like Shah Jahan rendered patronage as well as support. Many poets in

Pakistan such as Zafar Iqbal, Sir Mohammed Iqbal, Faiz Ahmad Faiz, Munir

Niazi and Saifuddin Saif contributed their efforts for the Urdu

language.

Dialects and languages

After the

independence of

Pakistan

in 1947, when the Muslims refugees arrived in Pakistan, the values the

migrants brought with them varied from region to region, depending on

their origin. The Muslims refugees arrived from different regions often

speaking different dialects of the

Urdu language such as

Awadhi,

Khariboli,

Braj,

Bhojpuri,

[63] Bundeli,

Rekhta,

Hyderabadi or Dakhni, etc. These Urdu dialects were distinguished by their vocabulary, grammar, and pronunciation (

phonology, including

prosody), humor and slangs. Many Muslims refugees spoke regional languages such as

Gujarati,

Kutchi,

Marathi,

Konkani,

Telugu, etc. The Urdu

syllabus taught in the Karachi schools with its strong emphasis on

poetry and

literature helped to standardise Urdu in Karachi. These dialects and languages slowly merged to form a standard dialect closer to the

Awadhi dialect of the

Urdu language over the decades. Even the Urdu dialect of Karachi is very diverse, and some neighborhoods such as

Nazimabad has its own

accent that is different from the

Orangi speech; family background, and educational level also has an influence on the language spoken by a person

[citation needed].

The

Urdu language spoken in

Karachi

has become gradually more divergent from the Indian dialects and

structure of Urdu, since it has engrossed many words, proverbs and

phonetics from the regional languages like

Punjabi Sindhi,

Pashto, and

Balochi[citation needed]. The pronunciation pattern of Urdu language also differs in

Pakistan and the

cadence and lilt are informal compared with corresponding Indian dialects

[citation needed]. The Urdu speakers in Karachi consider their accent as the standard dialect of the

Urdu language[citation needed]

Contributions to literature

Poetry

Muhajirs

brought their rich poetic culture along with them which they held in

their original states centuries ago prior to independence. Some of the

most notable ones historic poets are Mir Taqi Mir, Mir Aman Dehalwi,

Khawaja Mir Dard, Jigar Muradabad etc. Subsequent to independence, many

notable Urdu poets migrated to Pakistan, besides a large number of less

famous poets, authors, linguists and amateurs. Consequently, Mushaira

and Bait Bazi became a part of the national culture in Pakistan. Josh

Malihabadi, Jigar Moradabadi, Akhtar Sheerani, Tabish Dehlvi, Nayyer

Madani and Nasir Kazmi are a few of the noteworthy poets. Later, Jon

Elia, Parveen Shakir, Dilawar Figar, Iftikhar Arif, Rafi Uddin Raaz and

Raees Warsi became noted for their distinction.

Prose

With the emergence of Muhajirs in urban areas of Pakistan, Urdu virtually became the

lingua franca. The country's first Urdu Conference took place in Karachi in April 1951, under the auspices of the

Anjuman Taraqqi-i-Urdu. The Anjuman, headed by

Maulvi Abdul Haq,

not only published the scattered works of classical and modern writers,

but also provided a platform for linguists, researchers and authors.

Among them

Shan-ul-Haq Haqqee,

Shahid Ahmed Dehlvi, Josh Malihabadi,

Qudrat Naqvi,

Mahir-ul-Qadri,

Hasan Askari,

Jameel Jalibi and

Intizar Hussain are significant names. Whereas

Akhtar Hussain Raipuri,

Sibte Hassan and

Sajjad Zaheer were more inclined to produce left-winged literature. Among women writers,

Qurratulain Hyder,

Khadija Mastoor,

Altaf Fatima and

Fatima Surayya Bajia became the pioneer female writers on feminist issues.

Contribution in science and technology

Muhajirs have played an extremely important and influential role in science and technology in Pakistan. Scientists such as

Ziauddin Ahmed,

Raziuddin Siddiqui and

Salimuzzaman Siddiqui, gave birth to

Pakistan Science and later built the

integrated weapons program, on request of

Zulfikar Ali Bhutto. Muhajir later forwarded to developed the

Pakistan's space program and other scientific and strategic programs of Pakistan. Many prominent scientists come from the Muhajir class including Dr.

Abdul Qadeer Khan, Dr.

Ishfaq Ahmad,

Ghulam Murtaza,

Raziuddin Siddiqui, Dr.

Pervez Hoodbhoy, Dr.

Salimuzzaman Siddiqui, and

Atta ur Rahman to name a few.

Contribution in art and music

The

Muhajir community brings a rich culture with it. Muhajirs have and

continue to play an essential role in defining and enriching

Pakistani culture and more significantly, music. Some famous Muhajir Pakistani musicians include:

Nazia Hassan,

Mehdi Hassan,

Munni Begum,

Ahmed Jahanzeb and

Maaz Moeed Zoheb Hassan. Muhajirs contribution has not been limited to pop but has spanned various

music genres, from traditional

Ghazal singing to rock. Muhajirs in Pakistan are also famous for their contribution towards the art of painting.

Syed Sadequain Ahmed Naqvi, one of the most famous painter of the world, was a Pakistani painter who was born in Amroha, India.

Contribution in business and industry

After partition in 1947 by the then British Government through

Indian Independence Act 1947;

the Muslims who immigrated to Pakistan were well educated and consisted

of journalists, urban intellectuals, professors, bureaucrats, lawyers,

teachers, academics and scholars etc. Although there were those that had

migrated who were the bourgeoisie consisting of merchants,

industrialists or capitalists, a large number of those who immigrated

from the rural areas and villages also consisted of labourers and

artisans. The eminent business groups that shifted from India to

Pakistan were Habib Bank, Muslim Commercial Bank, Orient Airways, among

others. Other businesses were established in Pakistan by some of the

notable figures as United Bank Limited, Hamdard Pakistan Limited, Schon

group. It is also known that besides founding several Governmental

organizations like State Bank of Pakistan, they played an influential

role in initiating the Atomic Energy Commission, Kanup, and several

other institutions. Muhajirs were also found in administration,

establishment and politics.

[64]

The initial business elites of Pakistan were Muhajirs. Prominents example of businesses started by them include

Habib Bank Limited, Hyesons,

M. M. Ispahani Limited,

Schon group etc. Nationalization proved to be catastrphpic for

Muhajir-owned businesses, and the final blow was delivered as a result

of discriminatory policies during the dictatorship of Gen.

Zia-ul-Haq.

In recent years, many Muhajirs have established their businesses in

Pakistan, with a focus on textile, garment, leather, food products,

cosmetics and personal goods industries. Many of Pakistan's largest

financial institutions were founded or headed by Muhajirs, including the

State Bank of Pakistan, EOBI,

Pakistan Industrial Development Corporation,

United Bank Limited Pakistan,

First Women Bank et cetera.

Contribution in sports

Muhajir

are active in many sports in Pakistan. Muhajirs are playing in the

Pakistani cricket team with well-known players such as Javed Miandad,

Saeed Anwar, Asif Iqbal, Mohsin Khan, Sikhander Bakht, Rashid Latif,

Basit Ali and Moin Khan.

[65]

There are now younger players like Asad Shafiq, Fawad Alam, Sarfaraz

Ahmed, Khurram Manzoor playing for the international team. Muhajirs are

notably involved in hockey, tennis, squash and badminton. Bodybuilding

and weightlifting are increasing in popularity among younger members of

the Muhajir community.

Cuisine

-

Nihari, the national dish of

Pakistan was brought to Pakistan by the Muhajir people from India

[66]

-

-

-

Kebabs are an important part of the ancient Muslim cuisine.

-

Faluda, an ancient Hyderabadi dessert.

-

-

-

-

-

-

Korma, a traditional cuisine originated from ancient Lukhnow royals.

-

Bihari Kabab, a traditional cuisine originated from

Bihar.

-

Chilli Sauce and Yougurt chutney – Biryani Accompaniments

Muhajirs clung to their old established habits and tastes, including a numerous desserts, savoury dishes and beverages. The

Mughal heritage played an influential role in the making of their cuisine. In comparison to other native

Pakistani dishes,

Muhajir cuisine tends to use traditional royal cuisine specific to the

old royal dynasties of now defunct states of ancient India. Most of a

dastarkhawan dining table include

chapatti, rice,

dal, vegetable and meat

curry. Special dishes include

biryani,

qorma,

kofta,

seekh kabab,

Nihari and

Haleem,

Nargisi Koftay, Roghani Naan,

Naan,

sheer-qurma (sweet), qourma,

chai (sweet, milky tea),

paan and

Hyderabadi cuisine, and other delicacies associated with Muhajir culture.

See also

References

"POPULATION BY MOTHER TONGUE" (PDF).

External links

Kashmir and Sindh: Nation-building, Ethnicity and Regional Politics in South Asia. The total population of Pakistan is about 120 million, out of which 20 million have migrated from India

National Security: Imperatives and Challenges. There are 20 million Muhajirs in Pakistan (2004)

Understanding the Cultural Landscape.

Encyclopedia of the World's Minorities

The Man who Divided India: An Insight Into Jinnah's Leadership and It.

Nadeem F. Paracha. "The evolution of Mohajir politics and identity". dawn.com.

"Karachi Bloodbath: It is Mohajir Vs Pushtuns". Rediff. 20 September 2011.

"Don’t label me ‘Mohajir’". tribune.com.pk.

"‘Mohajir card’ – all key parties contesting by-polls using it". The News International, Pakistan. 20 April 2015.

Dr Niaz Murtaza. "The Mohajir question". dawn.com.

"MQM to observe ‘black day’ over Khursheed Shah's ‘Muhajir’ comment". Dawn. 26 October 2014. Retrieved 27 April 2015. Read 5th Paragraph

"Muhajir". WordSense.eu. Retrieved 27 April 2015.

"Muhajirs in Pakistan". European Country of Origin Information Network. Retrieved 27 April 2015.

Paul R. Brass (2003). "The partition of India and retributive genocide in the Punjab, 1946–47: means, methods, and purposes" (PDF). Journal of Genocide Research. p. 75 (5(1), 71–101). Retrieved 2014-08-16.

"20th-century international relations (politics) :: South Asia". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2014-08-16.

"Rupture in South Asia" (PDF). UNHCR. Retrieved 2014-08-16.

Dr Crispin Bates (2011-03-03). "The Hidden Story of Partition and its Legacies". BBC. Retrieved 2014-08-16.

Basu, Tanya (15 August 2014). "The Fading Memory of South Asia's Partition". The Atlantic. Retrieved 2014-08-16.

Oskar Verkaaik, A people of migrants: ethnicity, state, and religion in Karachi, Amsterdam: VU University Press, 1994

der Veer, pg 27–29

Eaton,

Richard M.'The Rise of Islam and the Bengal Frontier, 1204–1760.

Berkeley: University of California Press, c1993 1993, accessed on 1 May

2007

An Eighteenth Century History of North India: An Account Of The Rise And Fall Of The Rohilla Chiefs In Janbhasha by Rustam Ali Bijnori by Iqtidar Husain Siddiqui Manohar Publications

Imperial Gazetteer of India by W M Hunter

People of India Uttar Pradesh page 1047

Endogamy and Status Mobility among Siddiqui Shaikh in Social Stratication edited by Dipankar Gupta

Elphinstone, Mountstuart; Cowell, Edward Byles (1866). "The History of India: The Hindú and Mahometan Periods".

Jaques, Tony (2007). "Dictionary of Battles and Sieges". ISBN 9780313335372.

Sarkar, Jadunath (1992). "Fall of the Mughal Empire: 1789–1803". ISBN 9780861317493.

Mehta, J. L. Advanced study in the history of modern India 1707–1813

Conflict and Conquest in the Islamic World: A Historical Encyclopedia. Books.google.co.in. 2011-07-22. Retrieved 2014-08-18.

War,

Culture and Society in Early Modern South Asia, 1740–1849 – Kaushik

Roy, Lecturer Department of History Kaushik Roy – Google Books. Books.google.co.in. 2011-03-30. Retrieved 2014-08-18.

The Great Maratha Mahadaji Scindia – N. G. Rathod – Google Books. Books.google.co.in. Retrieved 2014-08-18.

History of the Marathas – R.S. Chaurasia – Google Books. Books.google.co.in. Retrieved 2014-08-18.

Glover, William J (2008). "Making Lahore Modern: Constructing and Imagining a Colonial City". ISBN 9780816650217.

Adamec, Ludwig W (2011-11-10). "Historical Dictionary of Afghanistan". ISBN 9780810879577.

Griffin, Lepel H; Griffin, Sir Lepel Henry (1905). "Ranjit Singh and the Sikh Barrier Between Our Growing Empire and Central Asia". ISBN 9788120619180.

Hunter, William Wilson (2004). Ranjit Singh: And the Sikh Barrier Between British Empire and Central Asia. ISBN 9788130700304.

Jaques, Tony (2007). "Dictionary of Battles and Sieges". ISBN 9780313335396.

Singh, Harbakhsh (July 2010). "War Despatches: Indo-Pak Conflict 1965". ISBN 9781935501299.

Nayar, Pramod K. (editor) (2007). The Penguin 1857 reader. New Delhi: Penguin Books. p. 19. ISBN 9780143101994.

Nayar, Pramod K. (2007). The great uprising, India, 1857. New Delhi: Penguin Books. ISBN 9780143102380.

Prof. M. Azam Chaudhary, The History of the Pakistan Movement, p. 368. Abdullah Brothers, Urdu Bazar Lahore.

Dhulipala, Venkat (2015). Creating a New Medina: State Power, Islam, and the Quest for Pakistan in Late Colonial North India. Cambridge University Press. p. 496. ISBN 978-1-316-25838-5. The

idea of Pakistan may have had its share of ambiguities, but its

dismissal as a vague emotive symbol hardly illuminates the reasons as to

why it received such overwhelmingly popular support among Indian

Muslims, especially those in the 'minority provinces' of British India

such as U.P.

Mohiuddin, Yasmin Niaz (2007). Pakistan: A Global Studies Handbook. ABC-CLIO. p. 70. ISBN 978-1-85109-801-9. In

the elections of 1946, the Muslim League won 90 percent of the

legislative seats reserved for Muslims. It was the power of the big

zamindars in Punjab and Sindh behind the Muslim League candidates, and

the powerful campaign among the poor peasants of Bengal on economic

issues of rural indebtedness and zamindari abolition, that led to this

massive landslide victory (Alavi 2002, 14). Even Congress, which had

always denied the League's claim to be the only true representative of

Indian Muslims had to concede the truth of that claim. The 1946 election

was, in effect, a plebiscite among Muslims on Pakistan.

"Port Qasim – About Karachi". Retrieved 14 June 2015.

"Karachi violence stokes renewed ethnic tension". IRIN Asia. Retrieved 2007-05-17.

Where Malayalees once held sway, DNA India

Khalidi, Omar (Autumn 1998). "From Torrent to Trickle: Indian Muslim Migration to Pakistan, 1947—97". Islamic Studies. Islamic Research Institute, International Islamic University, Islamabad. 37 (3): 339–52. JSTOR 20837002.

http://www.lse.ac.uk/asiaResearchCentre/_files/ARCWP04-Karim.pdf

"Stranded Pakistanis in Bangladesh not Pakistan's responsibility, FO tells SC". The Express Tribune. 30 March 2015. Retrieved 26 April 2015.

Delage, R., 2014. Muslim Castes in India. India: Books Ideas[1].

Kalim Bahadur (1998). Democracy in Pakistan: Crises and Conflicts. Har-Anand Publications. pp. 292–. ISBN 978-81-241-0083-7.

Tai Yong Tan; Gyanesh Kudaisya (2000). The Aftermath of Partition in South Asia. Routledge. p. 235. ISBN 0-415-17297-7. Sind

province itself became a centre of Muhajir immigration, with 57 per

cent of the population of Karachi [being Muhajirs] ... [They] 'were more

educated than the province's original Muslim population' ... It was

inevitable that a sense of competition and hostility between the two

communities would develop. As the Muhajirs made their presence felt in

the civil service the local Sinhis began to feel threatened ... In the

early years of Pakistan, the Muhajirs dominated the commercial,

administrative and service sector of the province ...the modern and

urbanised Muhajirs ... quickly established themselves.

Veena Kukreja (24 February 2003). Contemporary Pakistan: Political Processes, Conflicts and Crises. SAGE Publications. pp. 145–. ISBN 978-0-7619-9683-5.

Aqil Shah (2014). Army and Democracy: Military Politics in Pakistan. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-72893-6.

Veena Kukreja (24 February 2003). Contemporary Pakistan: Political Processes, Conflicts and Crises. SAGE Publications. pp. 144–. ISBN 978-0-7619-9683-5.

Omar, Imtiaz (2002). Emergency powers and the courts in India and Pakistan. England: KLUWER LAW INTERNATIONAL. ISBN 904111775X.

Riazuddin, Riaz. "Pakistan: Financial Sector Assessment (1990–2000)" (PDF). Economic Research Department of State Bank of Pakistan. State Bank of Pakistan. Retrieved 2 June 2012.

Kamala Visweswaran (6 May 2011). Perspectives on Modern South Asia: A Reader in Culture, History, and Representation. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 97–. ISBN 978-1-4051-0062-5.

Karen Isaksen Leonard (January 2007). Locating Home: India's Hyderabadis Abroad. Stanford University Press. pp. 37–. ISBN 978-0-8047-5442-2.

1998 census report of Pakistan. Islamabad: Population Census Organization, Statistics Division, Government of Pakistan, 2001.

"Accent and history". Language on the Move. Retrieved 14 June 2015.

http://www.jmi.nic.in/Events/Events05/pmpdp_report.htm

Nadeem F. Paracha. "Pakistan cricket: A class, ethnic and sectarian history". Retrieved 14 June 2015.